A classic form of torture is the practice of ripping off the fingernails of the victim until the information is forcefully and mercilessly extracted.

For a CLP reporter, a single fingernail torn out by the quick bite of a rusty folding chair, to the smell of unpalatable spaghetti, only evokes sympathetic questions.

And while such a bloody episode is more often dealt with by the likes of a fictional character played by George Clooney in the sociopolitical montage Syriana, my encounter was very real, covert activity notwithstanding.

On the contrary, my absurd experience at St. Gabriel’s hospital in Addis Ababa exposed me to the realities of healthcare in Eastern Africa, and provoked me to look further into healthcare availability and costs while comparing the Ethiopian system to healthcare realities in the United States.

It all started at the 7Up hotel and restaurant across from the CLP’s Addis Ababa home in a pocket of the 22nd neighborhood. We were planning on enjoying a late lunch. Tired of the fermented injera that we had consumed relentlessly for the past two weeks, we ordered a few plates of warm oily spaghetti and a round of cold St. George.

In my eagerness to take a closer look and whiff at the food served, I naturally scooted my chair closer to the table, tucking my hands between the two metal bars of the chair.

I felt a sharp quick tear, which soon turned to a numbing pain. My little finger had been mangled in the rusty joint of the chair. Choked up by tears, no words could come through my lips, except for a nonsensical screech, that my colleagues told me sounded like a distressed street cat. I assured the group that I was fine, and that they could continue eating. But suddenly none of the food seemed appetizing and Sarah insisted that we go to the nearest clinic or hospital.

Do you think my finger nail is even still there? I ask, looking down at the small, crimson ponds of blood oozing out of the sides of my finger.

“Ummm… I don’t know,” Sarah replied hesitantly, looking over at Jessica.

“Let’s just go see about a Tetanus shot,” said Jess avoiding the question.

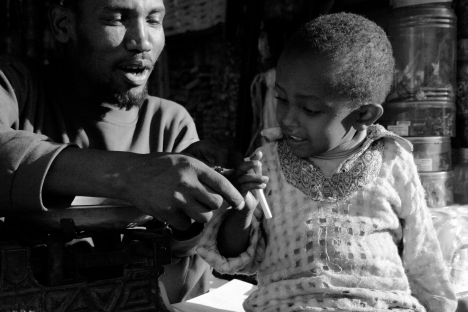

We soon arrive at the small, white private hospital just a block from our house. There were a few other people in the waiting room, all sitting patiently and calmly. I looked around, and didn’t see any other blood but the one that was gushing from my finger. Within only five minutes I was already meeting with a doctor, who began pouring water and disinfectant onto the wound.

I immediately thought about how long I’d have waited in the U.S. to see a doctor.

“I think your finger nail is still here,” the doctor said.

The cold antiseptic burned like fire, and sent shivers throughout my arm.

She swabbed my finger gently and looked at me curiously. She could tell that I was eager to ask her something.

Which was true, while I was there, I thought it’d be a good opportunity to interview her about some health issues related to our stories on sanitation and water, not to mention health concerns regarding traveling.

As a traveler in Africa in particular, health is a topic of discussion several times a day. It might go something like this:

“Don ‘t drink this water, you’ll get diarrhea.

“Ok, just bottled then. And what about this fresh lettuce?”

“No, no, that’s washed in the contaminated water.”

“Ok. But I miss salad.”

“Well, you’ll miss proper digestion too when you become a hotel for parasites.”

“I think I already have parasites.”

“Ok, well, let’s get some Zentel. Did you remember your malaria pill today?”

“Yes, and I have my yellow fever vaccination card so I can cross the border into Kenya.”

“Ok, good.”

My conversation with the doctor took a bit more serious tone.

“Do many people come in here because of water-related illness?” I asked.

She told me that a large percentage of her patients suffer from waterborne diseases by simply drinking the city water, mainly due to road construction, which has broken some of the water pipeline, exposing this water to dirt and contamination.

“Most people don’t believe they are sick because of the city water, so they don’t boil it,” she added.

In Ethiopia, less than 40% of the population has regular access to an improved water source, compared to almost 100% of the U.S. population, according to the World Health Organization.

Due to these poor sanitary conditions, 250,000 children die every year in Ethiopia. One woman Ernest and I spoke with in the poor slum of Kechene in Addis told us how she had lost her granddaughter because of a water-borne disease. Where she lived, she had to walk 45 minutes to find a spring which was still probably too dirty to drink by most standards.

We also met NGO workers at CARE international who work on improving malnutrition in children around the border town of Moyale. With more than half of children under five severely malnourished, many Ethiopians chronically suffer from a lack of regular food.

There is no doubt that Ethiopians suffer from poverty and disease at an exponentially greater rate than Americans. But like my surprise regarding the accessibility of healthcare here it’s important to examine the benefits and drawbacks of both places – maybe with some lessons to learn in the process.

While most Americans have enough food to eat and drink, it is difficult to find organic meat or vegetables at affordable prices. Processed fast food, with its lack of nutrients, is much more accessible to America’s poor, who often suffer health problems as a result.

Ethiopia on the other hand, raises and serves grass-fed beef and organic vegetables by default. You won’t find a trendy, organic health food store here. Instead, market-fresh vegetables and fruits are found on almost every corner in Addis, and freshly butchered goats hang lifelessly in corner-store windows.

Unlike in America, most everyone here has access, though irregular, to organic meat and vegetables, but ironically, these foods raised in a natural environment without chemical fertilizers or pesticides are also often tainted by being irrigated or washed with contaminated water.

The same idea extends to healthcare costs. According to a Wall Street Journal-NBC Survey, almost 50 percent of the American public say the cost of health care is their number one economic concern. While an emergency room visit for someone without health insurance in the US can cost a month’s paycheck, in Addis, a trip to a private hospital is closer to $10 or $20. Public hospitals are even more accessible to Addis’ poor and working classes.

But in many remote regions of the country, Ethiopians have no access to hospitals private or otherwise and for many a few dollars in medical fees might as well be thousands. The grinding poverty of the country combined with a desperate lack of infrastructure creates an environment where most Ethiopian’s won’t live to see their fifty-fifth birthday.

Back at St. Gabriel’s hospital, with my interview completed and my finger snugly dressed I welcomed Sarah and Jessica as they arrived to pick me up.

“Well, the doctor thinks that my nail is still there. It’s just crushed,” I said.

“Actually,” Jessica said… “No.”

She held a single nail up in the air, the nail’s surface reflecting sunlight upon its incandescent curve.

“Oh…uh…really?” I laugh nervously.

“We found it under the chair. We just didn’t want to put you into shock.”

Laughing, I went and showed the doctor the nail. She was as dumbfounded as I was. I tucked the finger nail in my bag, and decided it might be a good thing to keep as a souvenir.

It’s easy to say that the healthcare system is far more advanced in the U.S. compared to a country like Ethiopia, and in many ways it is. But the reality is that the U.S. healthcare system is also in need of change. And like access to clean water, access to regular medical care—or lack there of—speaks to the level of development in a country.

My hospital visit in Ethiopia made me realize that while country is in great need of more medical resources, some services are more readily available and affordable than in the privileged nation of the U.S.

Losing a fingernail is the least of most people’s worries. Meeting those in Ethiopia who struggle daily with common yet potentially deadly diseases such as diarrhea and malaria makes me thankful for my health and the health of those around me more than ever. And it helps me understand the crucial issue of healthcare with a new depth.

Throughout the globe, it is up to us as individuals and our leaders, to help ensure the health and well being of all within our society. I know it sounds funny, but I still have that fingernail. I carried it all the way here from Africa to remember the experience and to remind me that as old systems die off, new ones can grow back.

© 2008 The Common Language Project

You must be logged in to post a comment.